I wanted to familiarize myself with the GNURadio environment and creatively implement some adaptive filter ideas, so I chose to write a flexible custom C++ module for spike detection and removal. The filter can track and attenuate multiple interferers as they overlap and drift around the frequency spectrum. It works on complex basebands, so it can be used to recover modulated RF signals as well as real-valued signals like EEG data.

Here is the Github repo for the project if you’d like to explore it.

architecture

I decided on a cascaded IIR structure to get deep attenuation of multiple interference spikes. Wanting to get clever with the tracking, I drew inspiration from a family of adaptive filters that update themselves based on the derivatives of their own equations in order to do it completely in the time domain. Most of the legwork can be done without expensive Fourier transform operations this way.

While I originally hoped this idea would be sufficient, it turned out that occasional forays into the frequency domain were still needed to detect spikes based on an amplitude threshold. When a notch is placed at a spike, it can follow the spike around via gradient descent without recomputing its central frequency. From this observation comes the two stages of the filter:

- Global Detection Stage: intermittently computes an FFT across a circular buffer of samples and detects newly emerged interference spikes as judged by a threshold multiplier of the mean input amplitude. New IIR notches are spawned at unhandled spikes, and old ones are pruned.

- Local Tracking Stage: once a notch is placed around an interference source, it performs a continuous update of the gradient of the output power of the overall filter with respect to a positive change in its center frequency $\omega$. This allows it to make decisions about how to adjust its own frequency in order to track drifting interferers without needing FFT.

tracking stage

Each notch is a first order IIR $$y[n]=x[n]-ax[n-1]+ray[n-1]$$centered at $w$, so $a=e^{jw}$. The zero sits on the unit circle for maximum attenuation, while the pole sits $1-r$ away from the zero and determines the bandwidth of the filter as configured by the user. This resembles the so-called CPZ-ANF architecture (constrained pole zero adaptive notch filter).

$p[n]=|y[n]|^2$ is the instantaneous power of the output after the filter is applied. By minimizing this based on the value of $\omega$, we can find the frequency where the filter attenuates the input the most – i.e, the frequency of the interference source!

At a given moment, we want to determine whether ${p}[n]$ increases or decreases when we increment $\omega$ by a small step. By making this determination and then choosing the direction that decreases $p[n]$, we will find the frequency of the narrowband interference. When $\omega$ is incremented based on its effect on ${p}$, it naturally follows the transition bandwidth of the spike to its center.

In order to understand how $p[n]$ is affected by a change in $\omega$, consider its partial derivative with respect to $\omega$. Since $p$ depends on the filter output $y[n]$, we can find $$\frac{\partial y[n]}{\partial \omega}=g[n]=-(ja)x[n-1] +r(ja)y[n-1]+rag[n-1]$$ Given $p[n]=|y|^2=yy^{*}$ (from the definition of the squared magnitude of a complex function given complex conjugate y*), $$\frac{\partial p[n]}{\partial \omega}=\frac{\partial (yy*)}{\partial \omega}=2ℜ(gy*)$$ Thus:

- If the value of $2ℜ(gy*)$ is positive, then output power increases if $\omega$ increases, so we decrease $\omega$

- If the value of $2ℜ(gy*)$ is negative, then output power decreases if $\omega$ increases, so we increase $\omega$

So given a small step value $\omega_\triangle$, we update $$\omega \leftarrow \omega-\omega_\triangle( \frac{\partial p}{\partial \omega})$$

Placing the notches at detected spikes and then letting them perform this computation per-sample is the essence of the filter.

some development notes

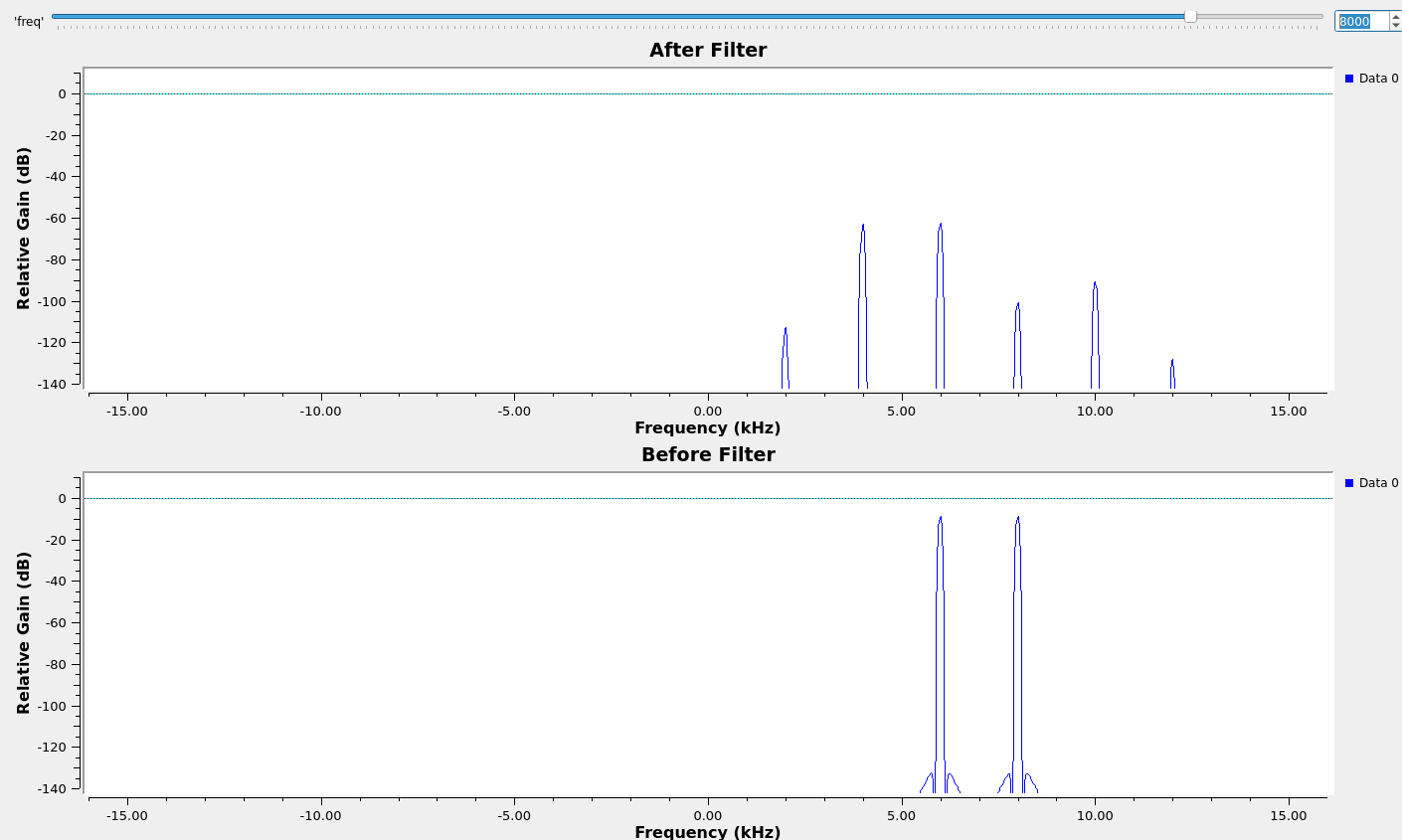

At one prototype stage, the adaptive filter was able to track and settle on a single stationary interferer. However, the use of a slower (every 8 sample) update rate for $\omega$ produced spectral lines at $f_s/8$ intervals. I fixed this by simply updating $\omega$ per-sample with no significant performance penalty, but it was a good lesson learned about the consequences of introducing periodic behavior into a filter function. I also imposed an upper bound of $50 Hz$ on how much $\omega$ could move per update, since this also contributed to some sideband generation.

At one prototype stage, the adaptive filter was able to track and settle on a single stationary interferer. However, the use of a slower (every 8 sample) update rate for $\omega$ produced spectral lines at $f_s/8$ intervals. I fixed this by simply updating $\omega$ per-sample with no significant performance penalty, but it was a good lesson learned about the consequences of introducing periodic behavior into a filter function. I also imposed an upper bound of $50 Hz$ on how much $\omega$ could move per update, since this also contributed to some sideband generation.

When multiple notches were implemented, sidebands also emerged despite smooth tracking. When I inspected the $\omega$ values for each notch, it seemed like dithering was being caused by very small oscillations of the notch frequency even when placed correctly in theory, contributing to both spurs and insufficient attenuation. Some approaches I tried:

When multiple notches were implemented, sidebands also emerged despite smooth tracking. When I inspected the $\omega$ values for each notch, it seemed like dithering was being caused by very small oscillations of the notch frequency even when placed correctly in theory, contributing to both spurs and insufficient attenuation. Some approaches I tried:

- Introducing a deadband (minimum $\omega_\triangle$) of 0.02 Hz required to update $\omega$. Larger update requests would still be made even if the the notch was placed correctly, so a minimal omega was not sufficient to predict meaningful updates.

- I tried a latch mechanism where enough consecutive small requests (< about 10Hz) ’locks’ the notch frequency, while enough consecutive larger requests (> 20Hz) ‘unlocks’ the notch and allows it to adapt meaningfully again. This introduced further issues – notches were unmotivated to adapt at all even when playing with thresholds, often falsely converging by settling on non-ideal frequencies due to latch triggering when its gradient was small. While the notches were stationary enough to prevent spurs, this resulted in very poor attenuation.

- I decided to try replacing the latch with a more elegant update smoother. This would use the gradient to persistently declare a target $\omega_\triangle$ and then continuously slew the update towards this value in order to prevent spectral lines emerging from discontinuously varying updates. By tuning the smoothing parameters, I achieved a maximum amplitude of -75dB for the interferers and sidebands in the worst (closest) case, and very successful attenuation when interferers were farther apart.

results

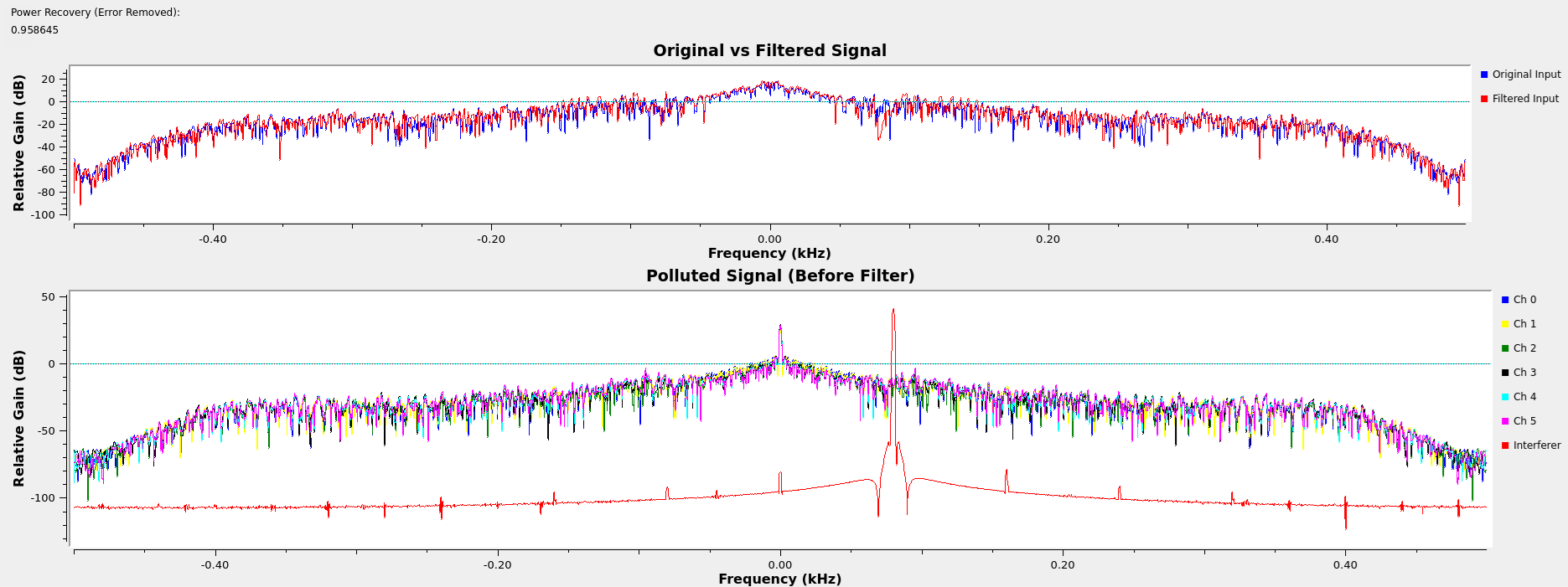

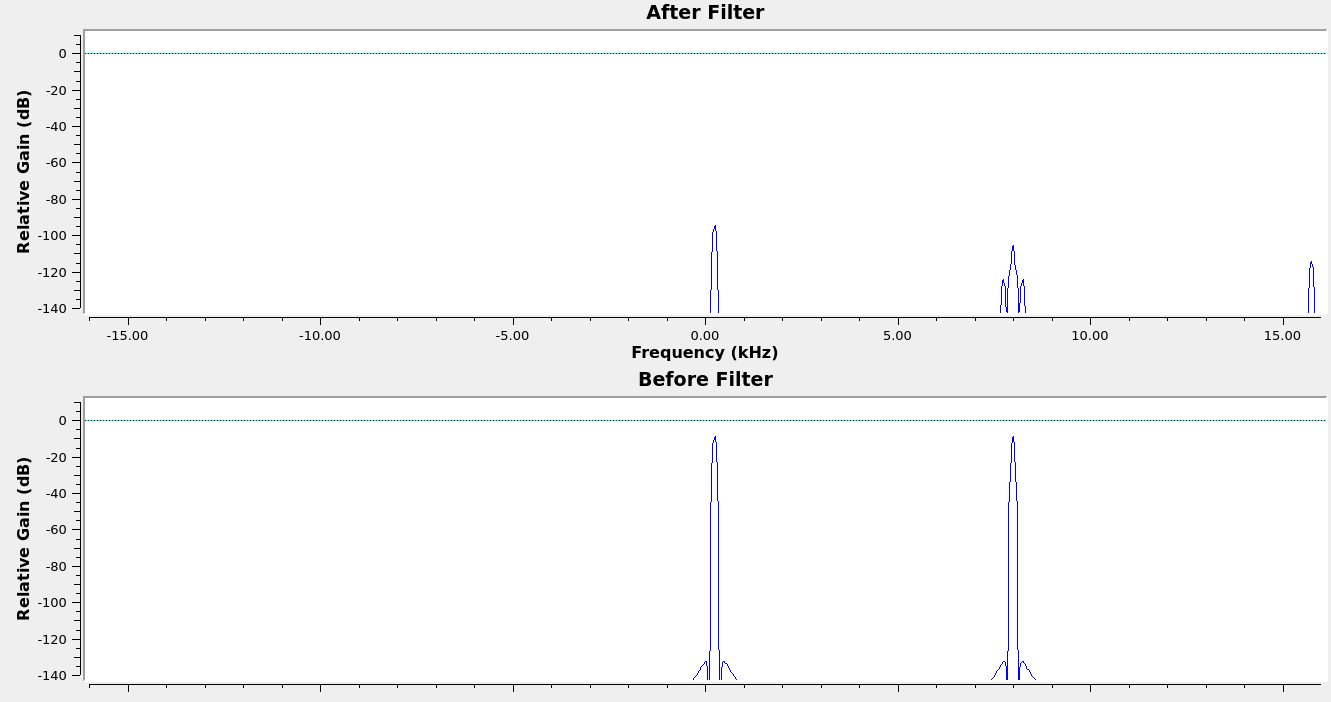

One unanticipated benefit of the cascaded architecture is that as the number of notches allowed to generate increases beyond the number of interferers, the extra notches will work to exponentially attenuate the small spurs still being produced by the primary notches. By allowing for a few extras beyond the number of spikes anticipated and with some threshold tuning, nearly perfect spectral power recovery was achieved across most test cases for various signal types.

noise

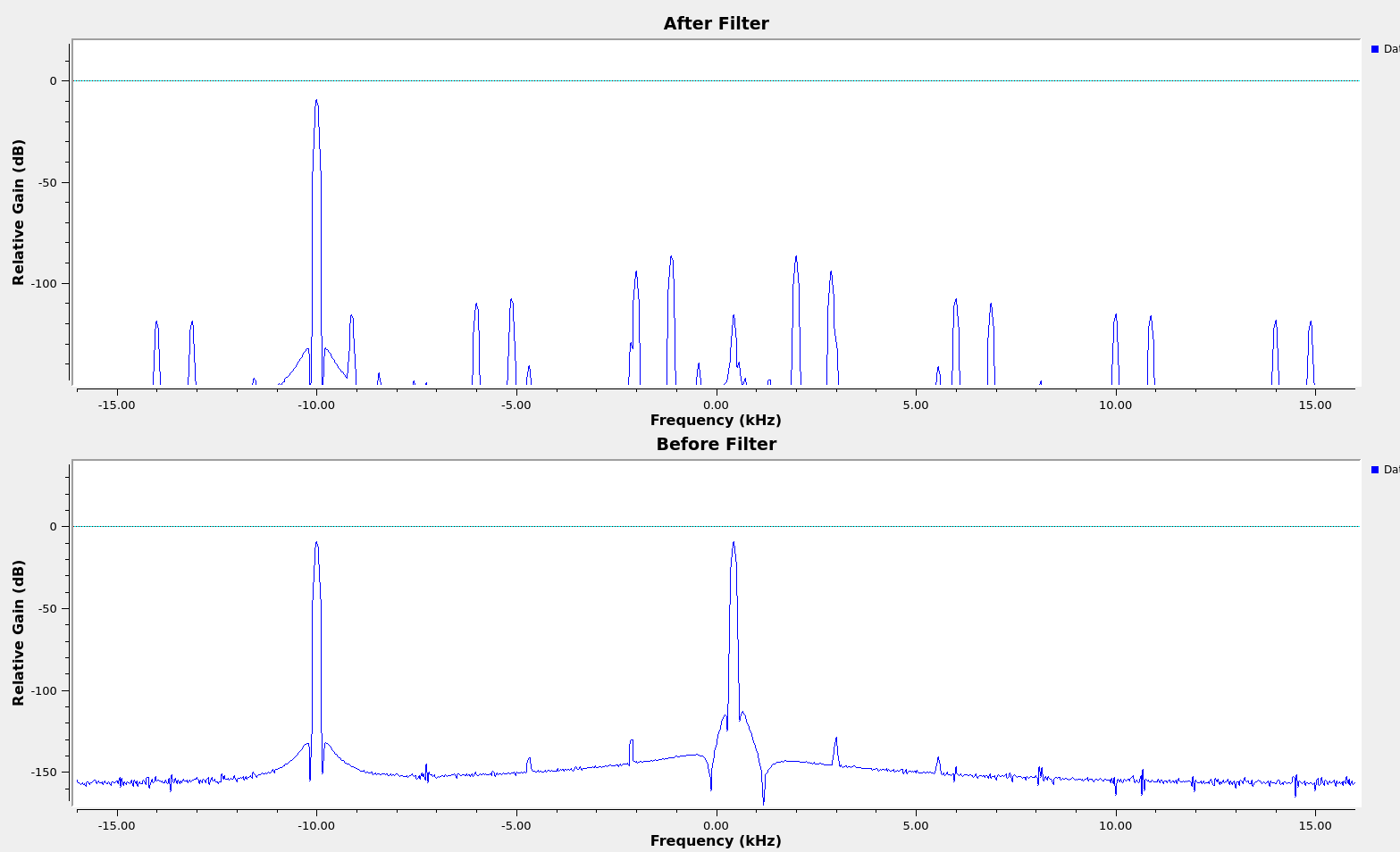

satellite

EEG